|

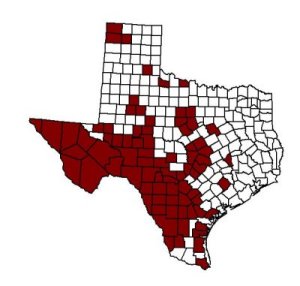

Map prepared by Greg T. Lewellen |

Puma concolor (Mountain Lion)

Written by

Jennifer Collar (Mammalogy

Lab--Fall 2003)

Edited by Karah Gallagher and Jennifer Bailey

|

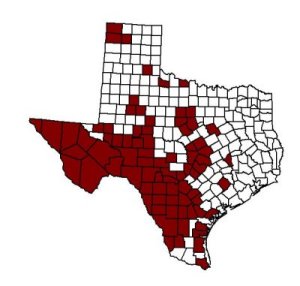

Map prepared by Greg T. Lewellen |

Mountain lions are a nearctic and neotropical creature with one of the most extensive distributions of all American terrestrial mammals. The mountain lion can currently be found in Central America, South America, British Columbia, Alberta, California, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, Utah, Nevada, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, Wyoming(Berg et al. 1983), Texas (Davis and Schmidly 1994), Oklahoma (Pike and Shaw 1999) and Arkansas (Nobel 1971). The mountain lion may be found in scattered locations from Mexico to Chile. The Florida panther (Puma concolor coryi) a subspecies of the mountain lion is found in southwestern Florida (Alderton 1998). A single mountain lion can have a home range of 40 to 200 square miles (Pierce and Bleich 1999). Mountain lions have been restricted to relatively mountainous and unpopulated areas due to hunting pressure and other environmental changes. However, populations are growing in the plains of Texas (Robertson and Atman 2000) Oklahoma (Pike and Shaw, 1999) and Arkansas (Clark et al. 2002).

The mountain lionís range is mainly in the southwest, south, southeast and central regions of Texas. Most sightings occur in Trans-Pecos Mountains and Basins, South Texas Plains, Edwards Plateau, and Cross Timbers and Prairies ecological regions of Texas. There has also been an increase in sighting reports in the Pineywoods, Gulf Coast Prairies and Marshes, Post Oak Savannah, and Rolling Plains ecological regions in recent years (Robertson and Atman 2000).

Photo courtesy Texas Parks & Wildlife © 2003

Photo courtesy Texas Parks & Wildlife © 2003

Physical Characteristics:

Mountain lions are large and slender with a distinctive long tail. Mountain lions range from 36 to 103 kg in males and 34 to 59 kg in females, with the males being about sixty percent larger than females (Busch 1996). The mountain lionís length ranges from 1.7 Ė 2.7 m in males and 1.5 to 2 m, with the males being longer than the females. The pelage is short and coarse in texture. The general coloration varies and can be tawny brown, shades of apricot, rust, lemon, and smoke. The belly is a pale buff. The throat and chest are whitish. Mountain lions have a pinkish nose with a black boarder that extends to the lips. The back of the ears, tip of the tail and stripes on muzzle are black with a vertical black stripe over each eye that disappears with age (Forsyth 1999). The limbs are short and muscular and the feet are broad with four digits on the hindfeet and five on the forefeet. The pollex is small and set above the other digits and the retractile claws are sharp and curved (Logan et al. 1986). The skull of the mountain lion is noticeably broad and short with a high forehead region. The rostrum and the nasal bones are very broad.

The dental formula of the mountain lion is i 3/3 c 1/1 p 3/2 m 3/2 with a total of 30 teeth (Nowak and Paradiso 1983). The mandible is short, deep, and powerfully constructed. The carnassial teeth are massive and long. The canines are heavy and compressed. The incisors are small and straight. The mountain lion has one smaller premolar on each side of the upper jaw than the bobcat (Lynx rufus) and lynx (Lynx canadensis).

Natural History:

Food Habits: Mountain lions are carnivores. Mountain lions eat mostly caribou (Rangifer tarandus), white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), elk (Cervus elaphus), bighorn sheep (Ovis Canadensis) and moose (Alces alces). Mountain lions have also been known to eat smaller creatures such as squirrels, mice, rabbits, muskrats (Ondatra zibethicus), porcupines (Erethizon dorsatum), beavers (Castor canadensis), raccoons (Procyon lotor), striped skunks (Mephitis mephitis), coyotes (Canis latrans), and birds (Alderton 1998). On rare occasions mountain lions have attacked livestock. Mountain lions hunt large prey in a very distinctive manner. The mountain lion moves within 15m of its prey and then leaps on its back, breaking the animalís neck with a powerful bite below the base of the skull. Most hunting is done in the early morning or evenings. The prey is often dragged to a specific spot and the mountain lion plucks away the fur before eating. Mountain lions can consume 20 to 30 pounds of meat in one sitting (Pierce and Bleich 1998).

Reproduction: Mountain lions are polygamous. Courtship and mating can happen at any time during the year. Gestation periods last from 88-97 days. Estrus in female mountain lions lasts about nine days. To let the males know she is in estrus, the female lets out a loud scream and rubs her scent against any nearby objects. Males respond with a similar scream (Busch 1996). Females usually give birth to 1 to 6 cubs, usually 3 or 4, every other year. The cubs are born in a den that is usually near water. The cubs are fluffy and spotted. Birth weight is usually one pound. After 10 days the cubs open their eyes, the ear pinnae unfolds, their first teeth erupt and begin playing. The cubs are fully weaned in about 40 days. The cubs remain with their mother for as long as 12 months. Males reach reproductive age at about 3 years of age and females at 2 Ĺ years. Males remain sexually active for approximately 20 years and females approximately 12 years (Burt and Grossenheider 1976).

Behavior: Mountain lions are solitary animals except during the breeding season (Grossman 2001). Mountain lions space themselves according to food supply and other essentials. Females with cubs live within a wide space used by the resident male. Mountain lions mark their territories using urine or feces by trees they then scrape. The mountain lion is primarily nocturnal. The mountain lion acquaints itself with its environment and food supply using its vision, sense of smell, and hearing. The mountain lion communicates with low-pitched hisses, growls, and purrs for attention. The loud, chirping whistle used by cubs serves to get the motherís attention. The mountain lion has summer and winter home areas in different locations, requiring a migration between ranges (Beier and Choate 1995).

Habitat: Mountain lions use a wide variety of habitats including coniferous forests, swamps, lowland tropical forests, mountains, dry brush country, grasslands, and any area with abundant prey and coverage. Caves, rocky crevices and dense vegetation serve as temporary shelter (Currier 1983).

Economic Importance for Humans:

Mountain lions have a considerable trophy value. Their pelt is either fashioned into a rug or attached to a wall. Mountain lions are hunted for sport, very seldom is the meat eaten by the hunter.

Mountain lions have occasionally been a threat to domestic livestock. They are also considered a potential danger to children and solitary adults, but in most cases this is extremely exaggerated (Manfredo and Zinn 1998).

Conservation Status:

The status of the mountain lion is not listed as rare, threatened or endangered under federal law, but is considered to a threatened species in some states. The Florida panther, however, is listed as Endangered under the Endangered Species Act (Busch 1996).

References:

Alderton, David. 1998. Wildcats of the World. Blandford, United Kingdom.

Beier, Paul, and David Choate. 1995. Movement patterns of mountain lions during different behaviors. Journal of Mammalogy 76:1056-1071.

Berg, R.L., L.L. McDonald, and M.D. Strickland. 1983. Distribution of mountain lions in Wyoming as determined by mail questionnaire. Wildlife Society Bulletin 11:265-268.

Burt, William H., and Richard P. Grossenheider. 1976. A Field Guide to the Mammals 3rd ed., Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

Busch, Robert H. 1996. The Cougar Almanac: a Complete Natural History of the Mountain Lion, Lyons and Burford, New York.

Clark, David W., Steffany C. White, Annalea K. Bowers, Leah D. Lucio, and Gary A. Heidt. 2002. A survey of recent accounts of the mountain lion in Arkansas. Southeastern Naturalist 1:269-279.

Currier, M.J.P. 1983. Felis concolor. Mammalian Species 200:1-7.

Davis, William B., and David J. Schmidly. 1994. The Mammals of Texas. University of Texas Press, Austin.

Forsyth, Adrian. 1999. Mammals of North America Temperate and Artic Regions, Firefly Books, New York.

Grossman, Elizabeth. 2001. Meet your new neighbor. Amicus Journal 20:3.

Logan, Kenneth A., Larry L. Irwin, and Ronell Skinner. 1986. Characteristics of a hunted mountain lion population in Wyoming. The Journal of Wildlife Management 50:648-654.

Manfredo, Micheal J., and Harry C. Zinn. 1998. Public acceptance of mountain lion management: a case study if Denver, Colorado, and nearbyÖ. Wildlife Society Bulletin 26:964-970.

Noble, R.E. 1971. A recent record of the puma in Arkansas. Southwestern Naturalist 16:209.

Nowark, R.M., and J.L. Paradiso. 1983. Walkerís Mammals of the World. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

Pierce, Becky M., and Vernon C. Bleich. 1998. Timing of feeding bouts of mountain lions. Journal of Mammalogy 79:222-226.

Pierce, Becky M., and Vernon C. Bleich. 1999. Migratory patterns of mountain lions: implications for social regulation and conservation. Journal of Mammalogy 80:986-992.

Pike, Jason r., and James H. Shaw. 1999. A geographic analysis of the status of mountain lions in Oklahoma. Wildlife Society Bulletin 27:4-11

Robertson, P., and C.D. Altman Jr. 2000. Texas mountain lion status report. San Antonio, Texas.